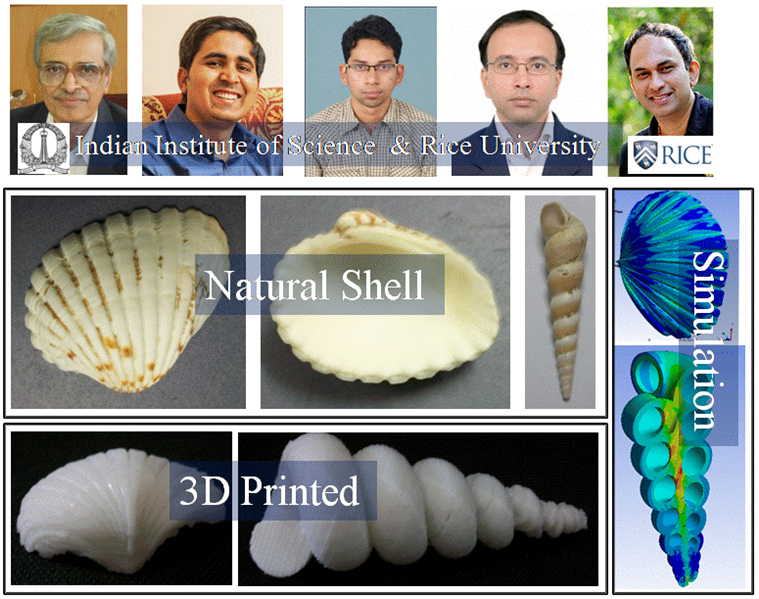

By modeling the average mollusk's mobile habitat, we are learning how shells stand up to extraordinary pressures at the bottom of the sea. The goal is to learn what drove these tough exoskeletons to evolve as they did and to see how their mechanical principles may be adapted for use in human-scale structures like vehicles and even buildings. In a teamwork spanning three departments and two institutions led by Professor Chattopadhyay and his colleagues at the Indian Institute of Science and of Professor Ajayan of Rice University, created computer simulations and printed 3-D variants of two types of shells to run stress tests alongside real shells that Dr. Tiwary collected from beaches in India.

They discovered that the structures that evolved over eons are not only generally effective at protecting their inhabitants, but also manage to redirect stress to locations where the soft creatures are least likely to be. These results appeared in a new online journal published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Science Advances.

The team took their research in a different direction to discover how seashells remain stable and redirect stress to minimize damage when failure is imminent. Using tools of finite element analysis and actual testing, they examined two types of mollusk:Bivalves with two separate exoskeleton components joined at a hinge (as in clamshells) and terebridae that conceal themselves in screw-shaped shells. In the case of clamshells, the semicircular shape and curved ribs force stress to the hinge, while the screws direct the load toward the centre and then the wide top.They found such evolutionary optimization allows fractures to appear only where they're least likely to hurt the animal inside. "Nature keeps on making things that look beautiful, but we don't really pay attention to why the shapes are what they are," said Chandrasekhar Tiwary, who along with Sharan started the work with Prof. Chattopadhyay, while Professor D.Roy Mahapatra at Aerospace Engineering provided the crucial inputs for finite element analysis.

"There are plenty of shapes that are even more complicated, and they may be even better than this for new structures," said Tiwary, the first author of the paper.

Other co-authors are undergraduate Sharan Kishore and graduate students Suman Sarkar. Professor Ajayan is chair of Rice's Department of Materials Science and NanoEngineering, the Benjamin M. and Mary Greenwood Anderson Professor in Engineering and a professor of chemistry.

Click here to read the open-access paper.

Scientific American and Popular Science covered the work in their recent issues. Click here to read the article on this work in Scientific American and here for the article in Popular Science.